Introduction

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere pretty much anything can be made into a puzzle. With a bit of work any everyday activity can be turned into a puzzle. While you’re getting started – it’s probably easiest to use / repurpose puzzles that you’ve seen in newspapers or used in gameshows or in mobile Apps. You can even go and buy a children’s spy book for inspiration. I would recommend testing individual puzzles in isolation with willing playtesters before included it in your Escape Game. The mantra is always, ‘Test, test, test!’ By testing you’ll be able to throw away puzzles that don’t work and improve those that do until you have fun and engaging puzzles that are related to your venue.

I don’t want to keep you completely in the cold – so wanted to give you some examples to get you started.

Before you do that – head over to head and read the general tips for puzzle creation:

Aside: General Puzzle Guidance

Examples

Codebreaking

Codebreaking is a great example of a puzzle to use in an Escape Room. People have this almost romantic vision spies sending secret messages to each other. Obviously, modern spy communication isn’t at all like this – but throughout history coded messages deciphered by hand have played an important role. In order to decode a message players need both the encoded message and the cipher (the algorithm required to decode it). Keep things simple for your player so it’s best to stick to simple ciphers that can be decoded in a few easy steps.

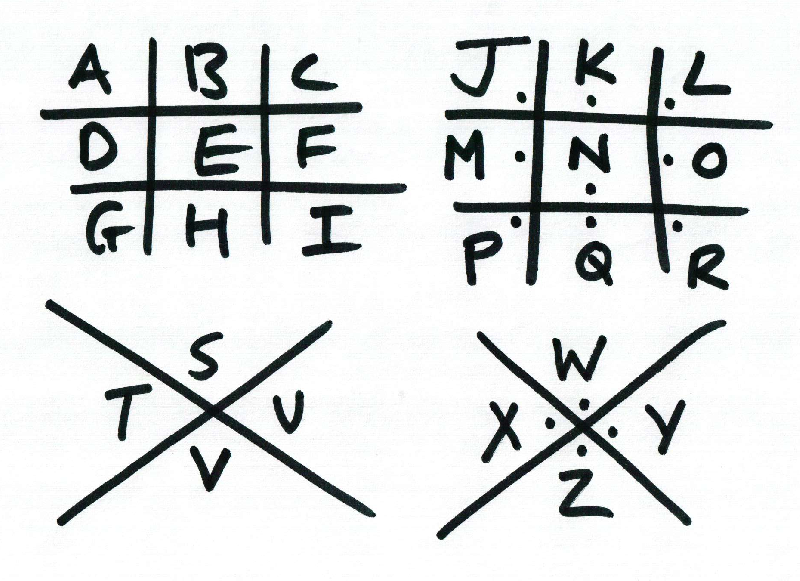

Example: Pigpen Code

A favourite of mine is the Pigpen Code which was used by the Freemasons in the 18th Century. It’s a cipher where a symbol is substituted for a letter. You might even remember this from when you were a child playing at being a spy.

We can use this to encode messages:

The question is how to provide these pieces to the player. Typically you want to give out the message and cipher separately. Often it’s best to give out the cipher in an obvious way and then the encoded message ‘hidden in plain sight’. Here’s an example of where a set of picture frames have been painted with the coded message.

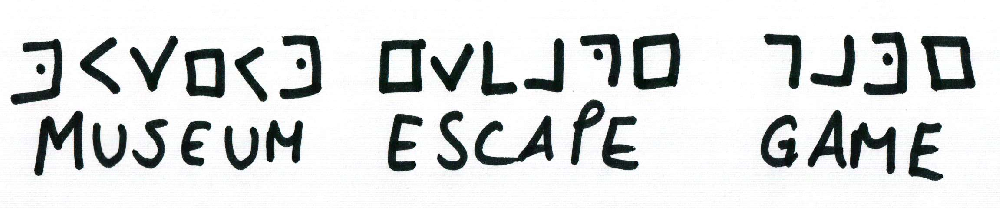

This is using a slight variation of the Pigpen that uses just squares:

There’s many more ciphers you can use – I thought this site at counton.org covers the basics of codebreaking quite nicely and might give you ideas for other ciphers.

Other ideas: there are so many code systems you can investigate. This image covers NATO phonetic, semaphore, panel signalling and flaghoist codes.

Missing Item

Again this is a classic puzzle that is used time and again in Escape Games. There is a set of items with one or more items missing – by identifying the missing item the player is able to determine a code.

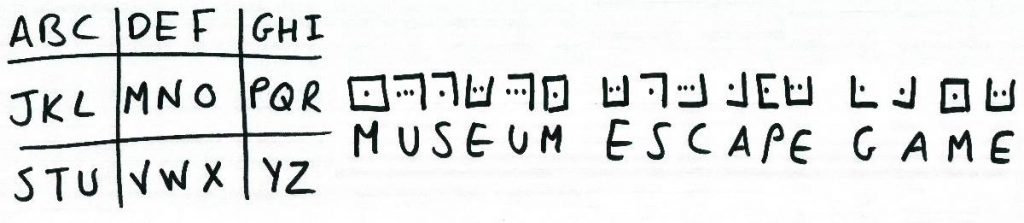

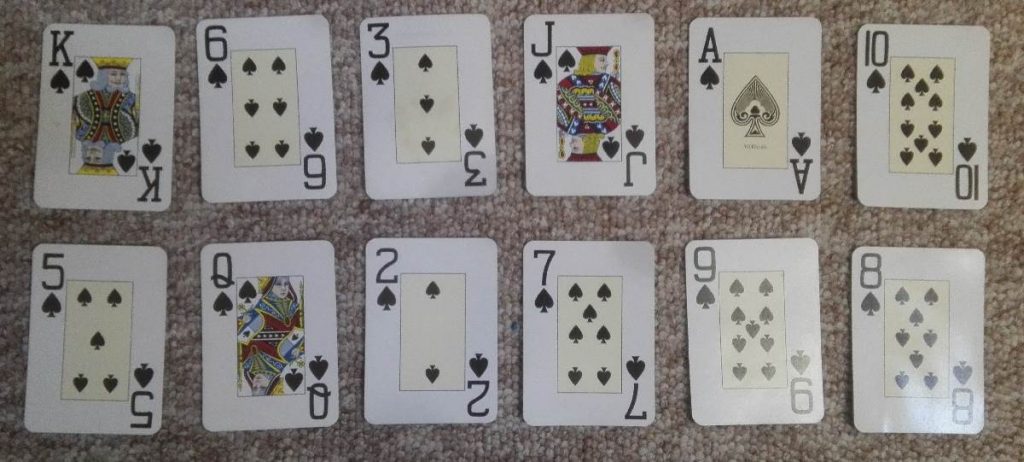

Example: Playing cards

Very popular and cheap to do. Playing cards are something that people are very familiar with – so it’s a relatively task for players to spot something missing.

The basic version is to remove a single card from a particular suit.

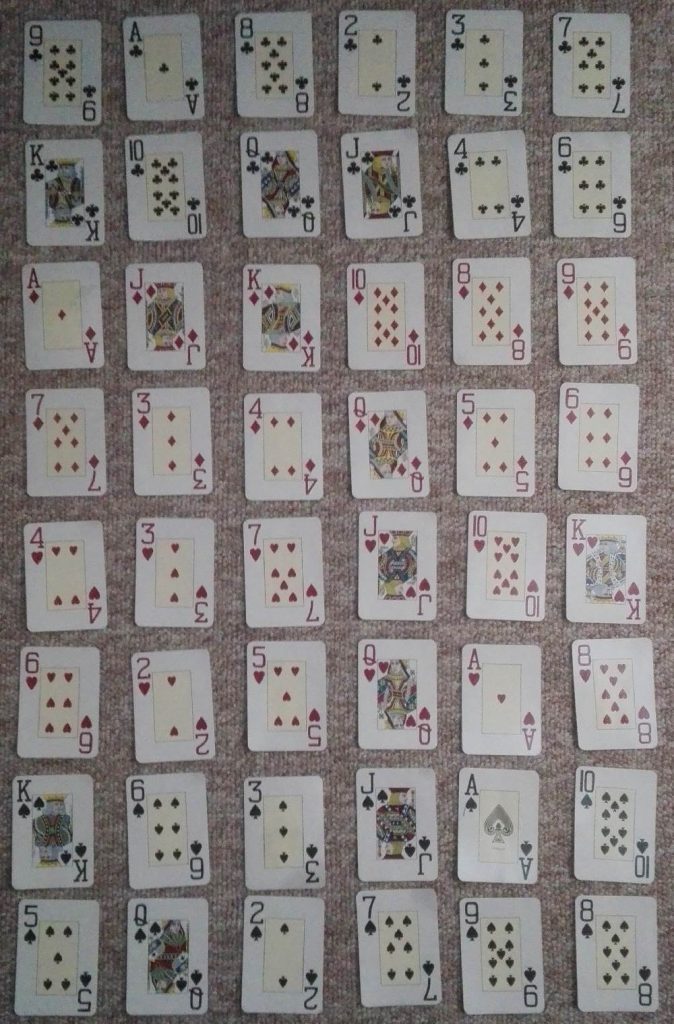

So it won’t have taken you very long to realise that the 4 of spades is missing. This is more obvious because you already know what the task it. However, if you come across a whole set of cards it might take you a bit longer. For example:

Again, not difficult for you know what the problem is and I’ve laid the cards out to keep it relatively simple.

It helps if there is a four digit padlock nearby that is preventing access to a box – as then our players are already on a hunt for puzzles that produce a 4 digit output. There’s an additional problem here as we don’t know the order of the 4 digits. It could be implied that the digits are from top to bottom (this is also alphabetical by suit name). I would suggest having something on the locked box (or lock itself) to help. Perhaps the suits in digit order used in the code. This gives a really clear message to the players that this box is in some way connected with card suits – when you come across some cards players begin to look for the connection.

To make this a more challenging puzzle – you can mix up the suits together so it’s less obvious that cards have been removed. It’s also common to see the cards laid out on a table in the form of a game in progress – perhaps it’s a poker game. This creates a fair bit of ambiguity about how these cards might be used.

Players will handle the cards and probably sort them into order. The problem then is how much work it is to reset them. It could be as simple as shuffling them and putting them back in a pack. Alternatives are to set up a card arrangement behind glass so they can’t be touched – or to include photos of game setups.

Example: Photo of scene with object missing

There’s lots of variations of the spot the missing object / spot the difference puzzle. This one uses a museum case with a selection of numbers museum objects. You need a photo of the case – but with an object removed (and ideally without object numbers). The task is then to find the correct case in the museum and then to identify the difference.

Here’s a photograph that the players find in one of their locked boxes:

As they will quickly realise an object has been highlighted in green. Only when you locate the correct object case are you able to interpret this.

It’s clearly object 6 that has been highlighted so we could use the number 6 in our combination or perhaps it points to something more complex such as understanding the label. You can create similar puzzles by having players read the labels in order to figure out what is the significant object.

Instead of doing with a photo and a physical location – it’s also possible to use two physical locations. You can set up two identical scenes (bar the slight differences) in two adjacent rooms and have players spot the difference. The two scenes should be far enough apart that you can’t see them simultaneously – this encourages co-operative play as players need to describe what they can see to each other.

Questions about museum objects / panels

Almost any object on display can become an input into a puzzle. You can use its object number in the case, some inscription that is written on it or its relationship to something else. This really gets players connecting with the museum objects. It has the other benefit that the objects are behind glass and generally safe from the player. These puzzles are dependent on what objects you have available but here are a few to get things started.

Example: Case of Coins

If we have a case that contains a selection of coins we have a number of puzzles that could be related to them:

- Simply count the number of coins

- Count number of coins with a criteria (perhaps year or king)

- Calculate the total value (probably needs a conversion chart)

Example: Timeline

Again a popular item in a museum. You could have one of these from any time period. Again these could be the basis of many puzzles either with straight-forward information or with more cryptic clues.

- Find the year of an event – this results in a 4 digit code

- Find two different dates and complete some simple arithmetic

- Use it to look for an event that happened in a particular year.

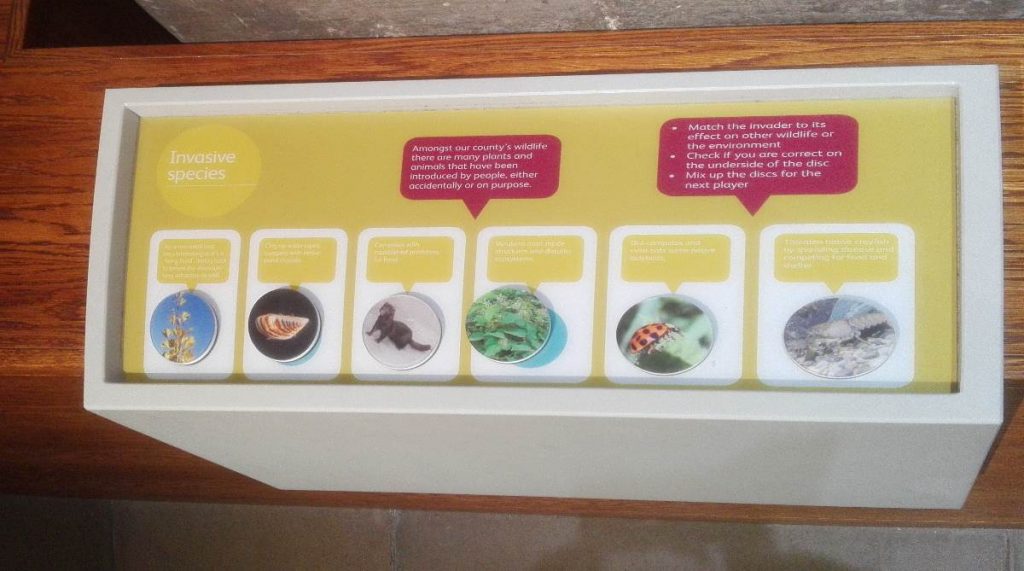

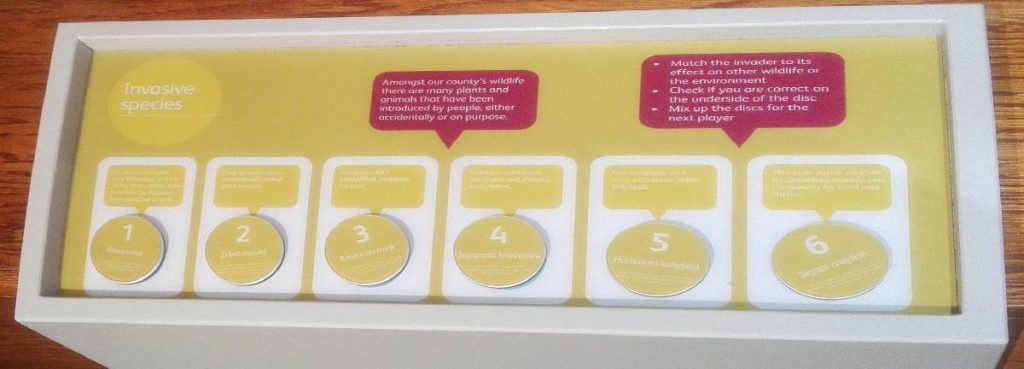

Example: Interactive with Flipped objects

You’re incredibly fortunate if you already have an interactive in your gallery that has pictures / text on one side and numbers on the other. There’s a little activity that players can solve in order to create a numeric combination.

The simplest one is to have either pictures that match those above (or if you want to make it harder descriptions). Only when the tokens are flipped over are the numbers revealed:

Example: Use existing inscriptions

Here’s an example for the British Museum. Although I appreciate we’re not all fortunate enough to have acces to ‘The Franks Caskett’. Players find a clue that looks like this:

It’s somewhat symbolic (I’ve added the name to make like much simpler for players to find). Clearly an area in green has been highlighted which the players should realise is of significance.

This would focus the players on this area of runes:

This set of runes could be the answer to a puzzle or players could be tasked with interpreting the runes and understanding what it means.

Audio Puzzles

Lots of examples here from using lyrics in songs to identifying animals by their sound. Here’s two audio puzzles that were used in Deep Secrets game.

Example: Shopping List Puzzle

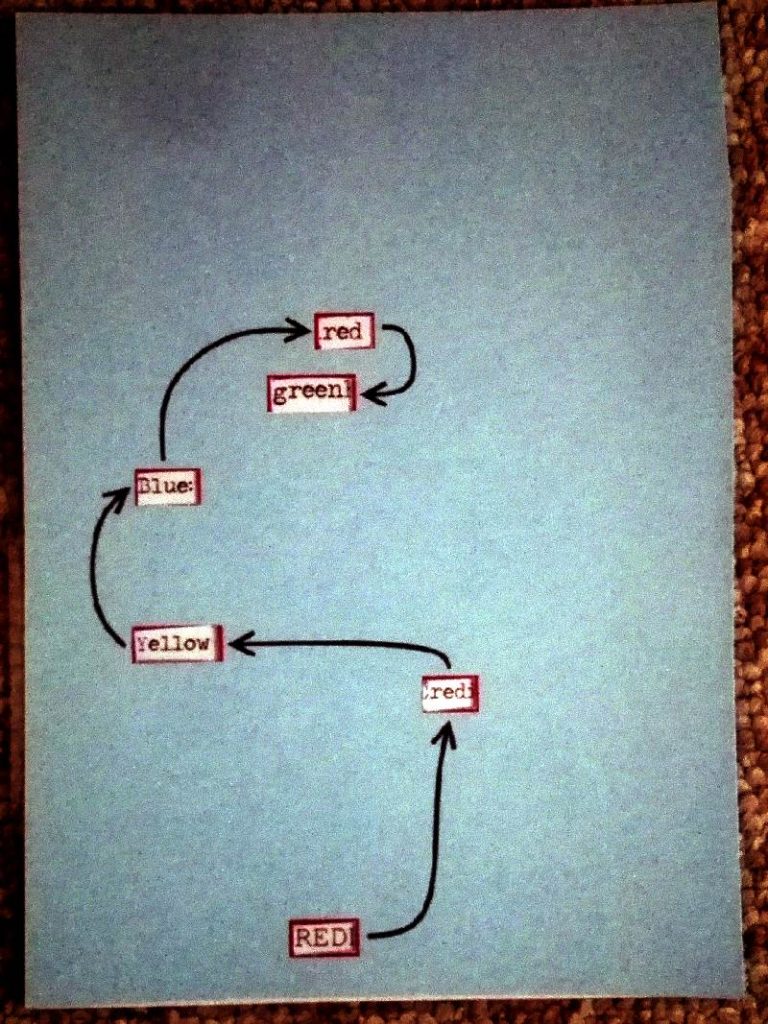

This was the first puzzle in the game so it was kept very simple. Players knew they were looking for a sequence of 6 colours (a combination of red, green, blue and yellow). Towards the end of the first telephone communication players here a request to collect a list of objects. If they are reasonably observant they will notice the list contains 6 items.

It’s simply a case of noting down the colour of each food item to create the 6 colour sequence.

Example: Morse Code Puzzle

This puzzle appears later in the game and is a straight-forward Morse code look-up. Players are listening for the letters R, G, B and Y to indicate the colours. Players can find a Morse code chart written in UV pen on the rear of a newspaper article.

This was a more difficult problem than anticipated. I’d already slowed things down more than I felt it needed – however as the letters sound quite similar players get easier confused. If you get just one wrong in a 6 colour sequence you still get no feedback as to what went wrong. It also appeared quite late in a long message – so if you weren’t sure you had to listen lots of story before you got back to the Morse code. These things are easily fixed if this game is run again.

It’s also possible to convert this Morse code puzzle into sight or touch based. Morse code (short and long pulses) works just as well through pulsing light or vibration motor.

Create Combinations from Instructions

Example: Colour in Squares

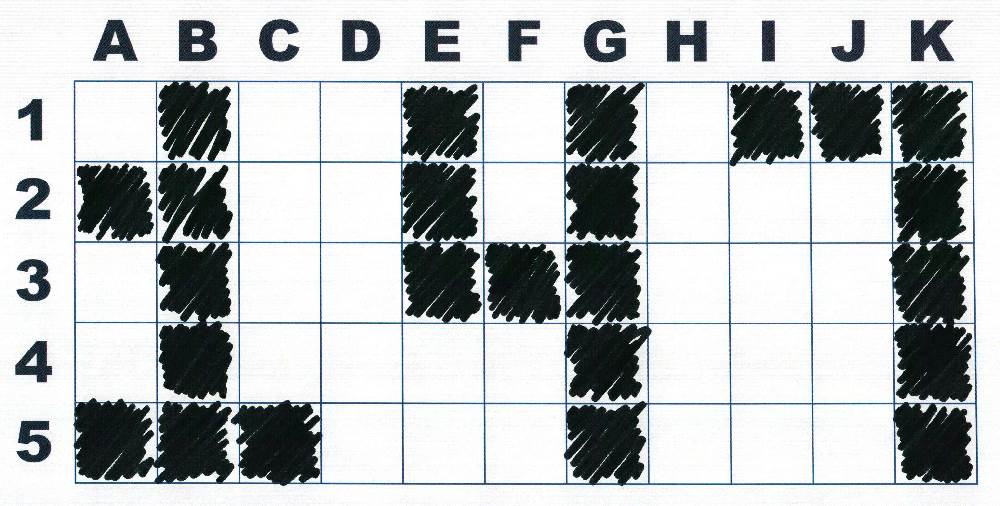

Again this a way of taking a series of clues and converting them to a 3 / 4 digit combination. The basic version is to supply players with a grid and then the clues lead them to colouring different squares. When you look at the grid as a whole you should see a number or letter combination.

Here’s 3 clues that you could find separately. Obviously, they don’t need to be as obvious as this. Perhaps there is a fake receipt or menu that has these things circled. It’s even possible to do this as a fake battleships game.

Once you colour in the segments you should have:

Example: Seven Segment Display

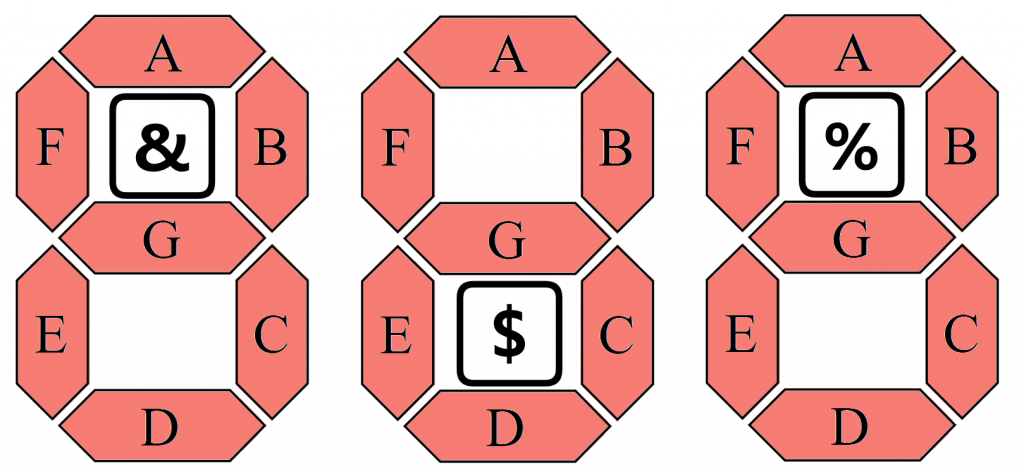

This is an almost identical puzzle but using a 7 segment display (as found in calculator displays).

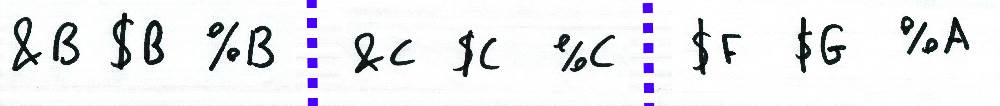

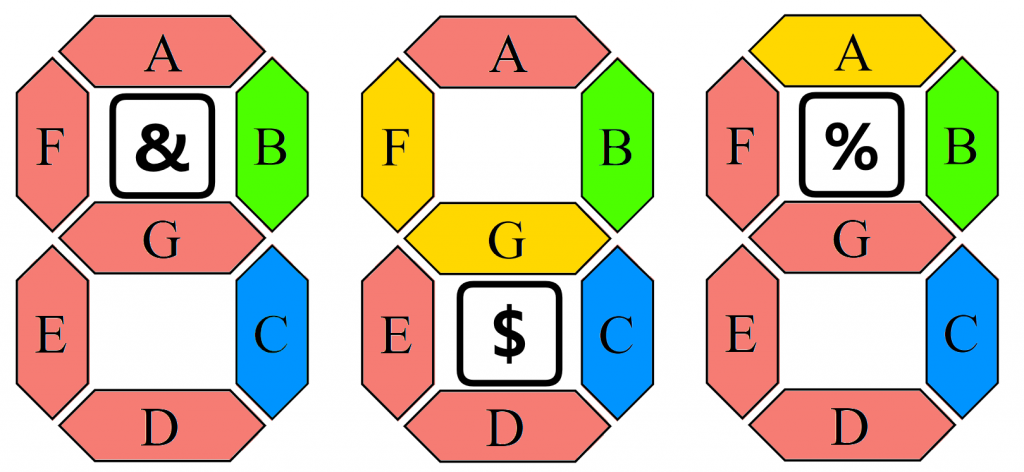

Below are the three clues. A symbol: &, $ or % is used to denote which of the 3 seven-segment displays we are interested. Then the letter denotes which segment to light-up / fill in.

The answer to this puzzle is:

As you can see I’ve been slightly mean – as after two clues you might already have the answer 111. It’s only when you get the final clue do you see that its: 147

These work well as puzzles as they are simple to solve – but the original clues are a long way from the answer – so it can playfully frustrate.

I’ve seen variations of this using wooden lacing boards / cross stitch. So players are provided with a length of cord and by going through holes in a wooden board allow you to create figures that resemble numbers.

Masks

Masks are again very popular in Escape Rooms. You might block some of the light from a spot light in order to highlight a number of important objects in a room. The principle is exactly the same when using paper / cardboard masks.

Example: Paper Mask

This is another puzzle taken from Deep Secrets. Right at the beginning of the game you are provided with a newspaper article which hints at the story. Towards the end of the game you find a mask which can be placed over it. You’ll notice there are a few words misspelt to create colours – this provides a hint to the players that at some point they will be extracting colours from it in some way.

Often players have forgotten about the newspaper article as it was used such a long time ago. This means that when the mask appears players start placing it over all the other paperwork clues they’ve collected. It’s slightly harder because the mask (intentionally) doesn’t have an up direction and it’s natural for players to use it flowing downwards. When placed together in the right orientation players are able to read the colour code sequence off it.

Within a museum setting you can use the same puzzle – either over paper clues you provide or over items already in the museum such as text panels. You might need to give a clue as to where the mask should be used so that players aren’t checking every single panel in your museum!

Jigsaw Solving

I’m not a huge fan of using jigsaws but they are pretty standard fodder in Escape Rooms. The nice part is that players can collect pieces of the jigsaw throughout the museum.

It’s often used as a way of combining puzzles together into an overarching puzzle. For example, each time a player opens a box – in addition to finding the next clues players also find a few bonus jigsaw pieces.

Even without all the pieces players can begin to put the jigsaw together and perhaps guess at the answer. This gives players a task to be working on – while they also know what they are looking for.

Either players build up a jigsaw that has a visual clue to the next lock (e.g. numbers circled in a picture) or they flip the puzzle over to reveal a further task.

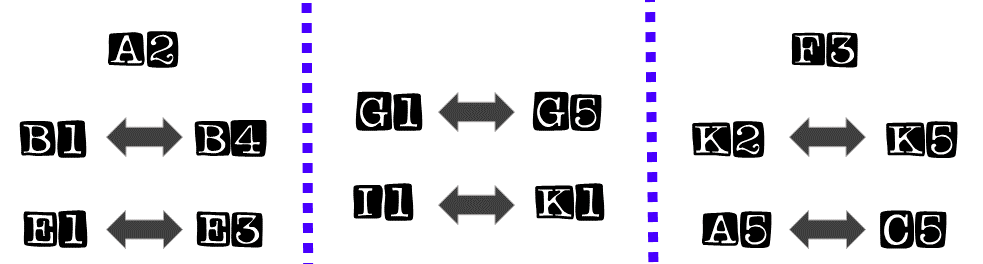

Combine Puzzles into one combination for a single Lock

If you want to really simplify things then you could combine multiple puzzles which produce a single 4 / 5 / 6 digit code. In addition you also need a puzzle that specifies the order of these digits. Giving you anywhere between 5 and 7 individual puzzles.

The advantage of this method is that you could keep just a single locked box safe on the desk in reception. This means you can still have physical rewards at the end of the game and it is easier for museum staff looking after the reception area to reset the single location. Also, the museum staff can offer congratulations to the players providing them with an ending and can use the process to engage visitors in other activities.

Wrap-up

So hopefully this give you an idea of the types of puzzles you can make in response to your museum. This is really only scratching the surface and the more you get into making puzzles the more you’ll begin to see them everywhere.

Next Steps

You probably came here from the pre-production stage. So lets jump back there and carry on with blocking out our Escape Room.