This online murder mystery was created for Newark Museum of Art. Keep an eye for when they are next running it.

Introduction

WKCC is a game that presents an interesting design challenge: How to to fuse Murder Mystery full-motion-video experience alongside Escape Game style puzzles. It is a Zoom-based 90 minute experience for small teams. Most teams spend a little over 60 minutes of time in-game but there is also the game introduction, ending and placing them into break-out rooms which takes about 15 minutes.

Story Overview

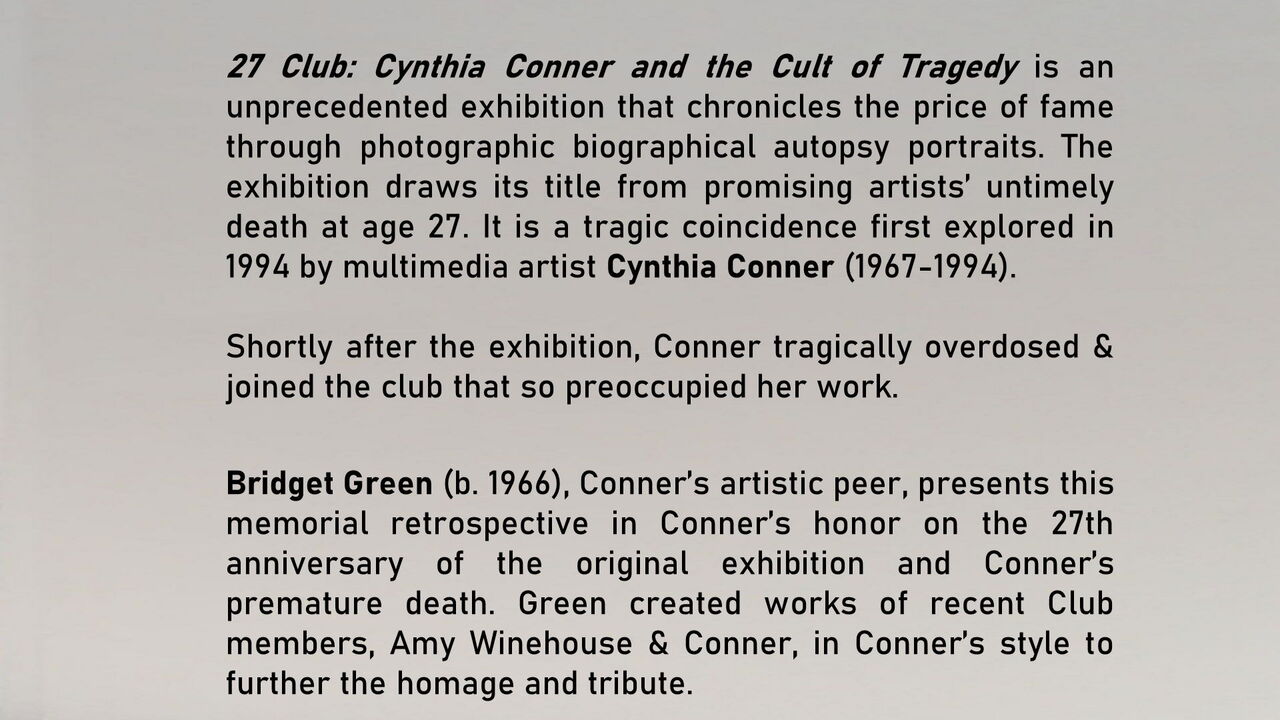

27 years ago

27 years ago the body of artist Cynthia Conner was found in the Old School House - an out-building in the gardens of the Newark Museum of Art. At the time the Coroner ruled it as a drug overdose - Cynthia had been a frequent user and it’s thought she was using a new supplier.

This was Cynthia’s break-out exhibition and one that was hoped to be the beginning of a very promising artistic future. The strange coincidence was that she was focusing on the ‘27 Club phenomenon’ - famous artists and musicians (such as Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix) that died at the tender age of 27! So, Cynthia’s untimely death had meant that she became the newest member of this club.

Was Cynthia’s death an unfortunate accident or perhaps the ultimate artistic expression? There are some that believe there was something more suspicious to it.

Here’s Nathaniel - one of our suspects to tell you more!

Present Day

We’re now 27 years on in the present day and the museum is having a retrospective about Cynthia’s short career. The exhibition has been extended by the work of Cynthia’s friend and peer, Bridget, who has painted further artworks in Cynthia’s style. Guests at the event include those who were at the original exhibition 27 years ago - here to pay their respects to Cynthia.

But, this is perhaps the only time to drag up the ghosts of the past. If this was something more than just a drugs overdose there’s not going to be a better time to investigate.

Gameplay

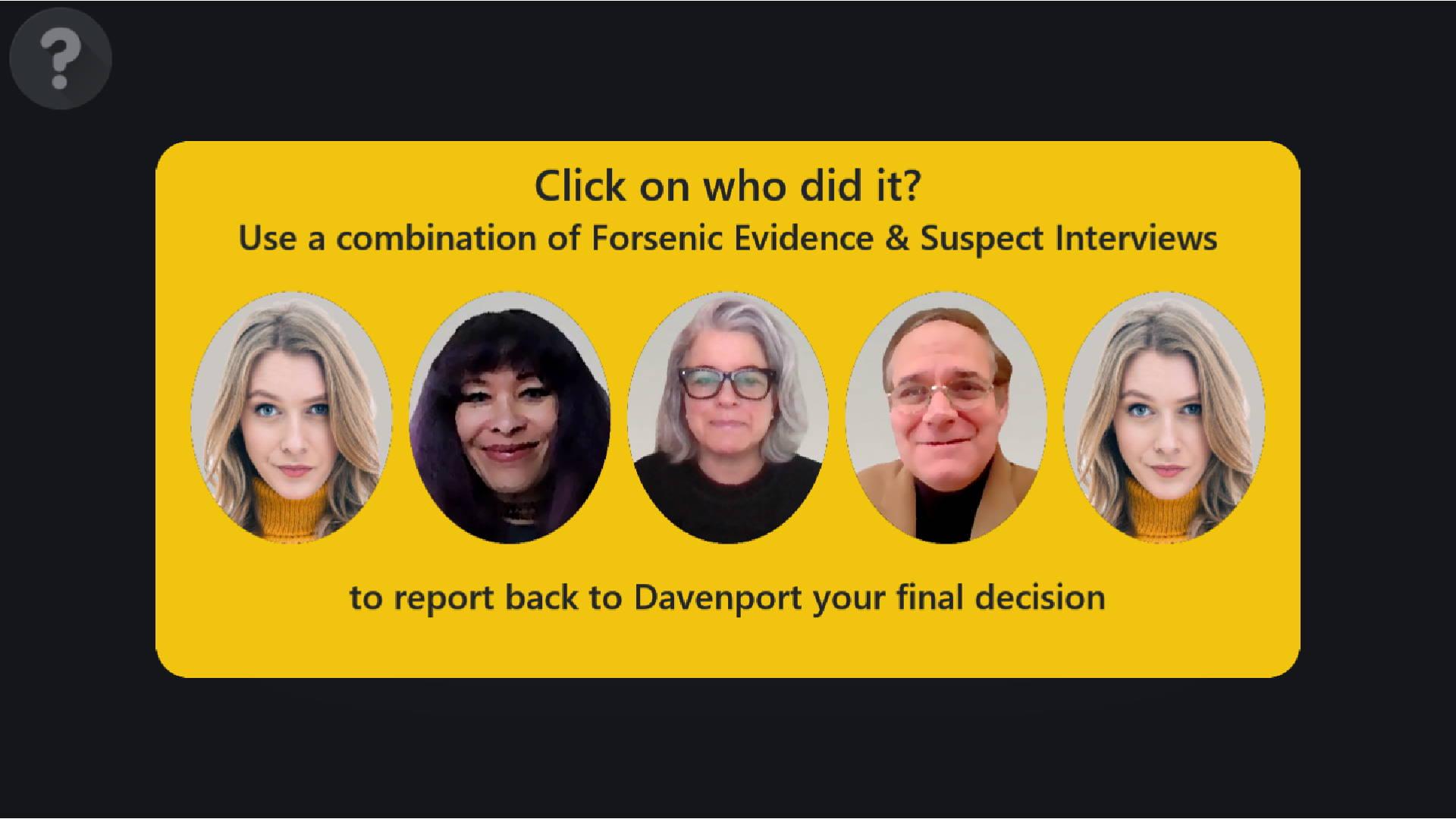

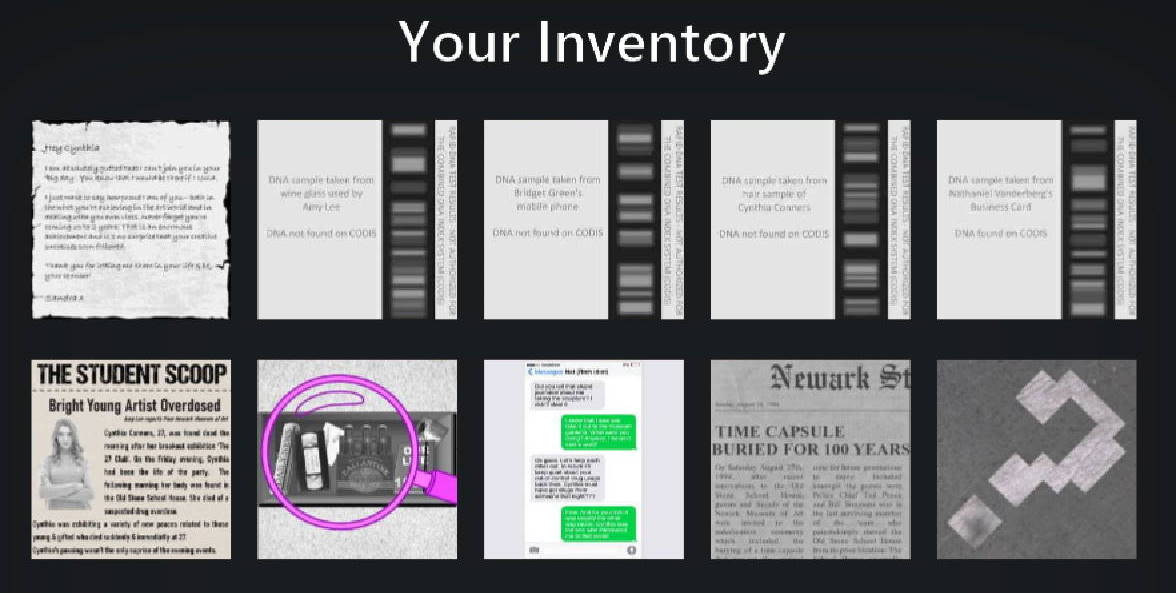

Players work in small teams to explore the museum and speak to the guests who attended 27 years ago. It uses a point-and-click style interface to walk around the venue, interact with puzzles and video to allow players to talk to the suspects and present them with evidence.

3 Act Structure

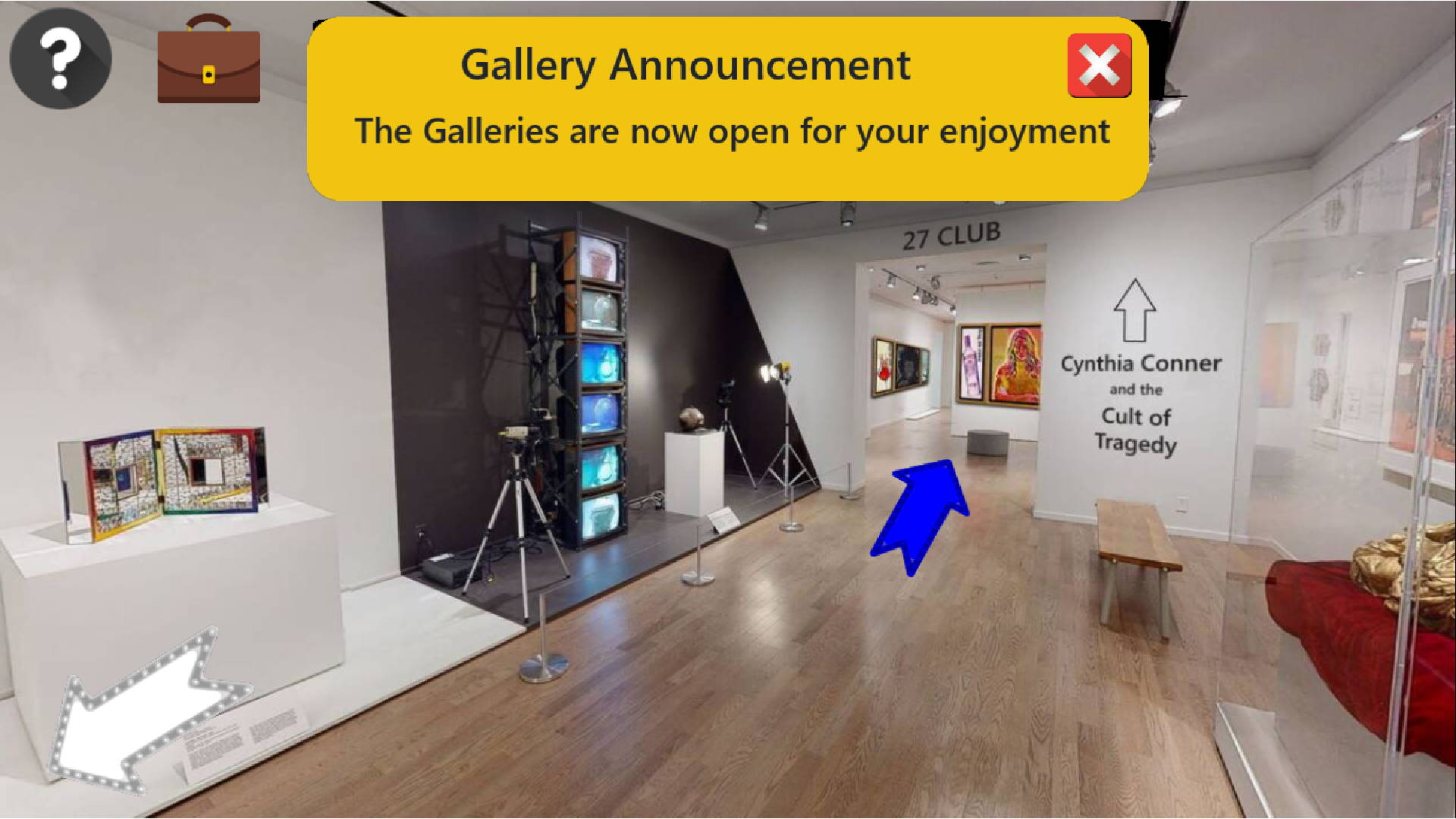

As with many of my other games this uses a 3 act structure. Each act opens a new area of the museum to explore and the suspects move around. Usually, in a 3 Act structure, Acts 1 and 3 would be much shorter than 2. That hasn’t really happened due to the changes that we made during playtesting and each Act takes roughly the same time.

Each Act is broadly set in a different environment. Act 1 in the museum galleries, Act 2 in the Ballantine House and Act 3 in the garden and outbuildings. I think this helps to give a sense of progression to the players.

There are two ways to play the game.

- Allow teams to take as long as they want

- Allow teams a fixed length of time

In the case of option 2, Davenport will reappear and then the players will have to make a final accusation based on the evidence they have collected so far. It’s easier to come to the correct conclusion with all the evidence collected and analysed.

Act 1 - Meet the suspects and explore the artwork (in the museum)

Act 2 - Interrogation (in the Ballantine House)

Act 3 - Forensic Evidence (in the gardens)

At the end of each act the players are asked to predict whether any of our suspects are responsible for Cynthia’s death or if it was caused by Cynthia herself - either accidentally or by suicide. These decisions are saved and presented back to the players at the end of the game to see how their thinking has changed throughout.

Example Puzzles

I’ve chosen two that are very much equipment based - so they are puzzles that you’d find more in a Point and Click Game rather than an online Escape Game.

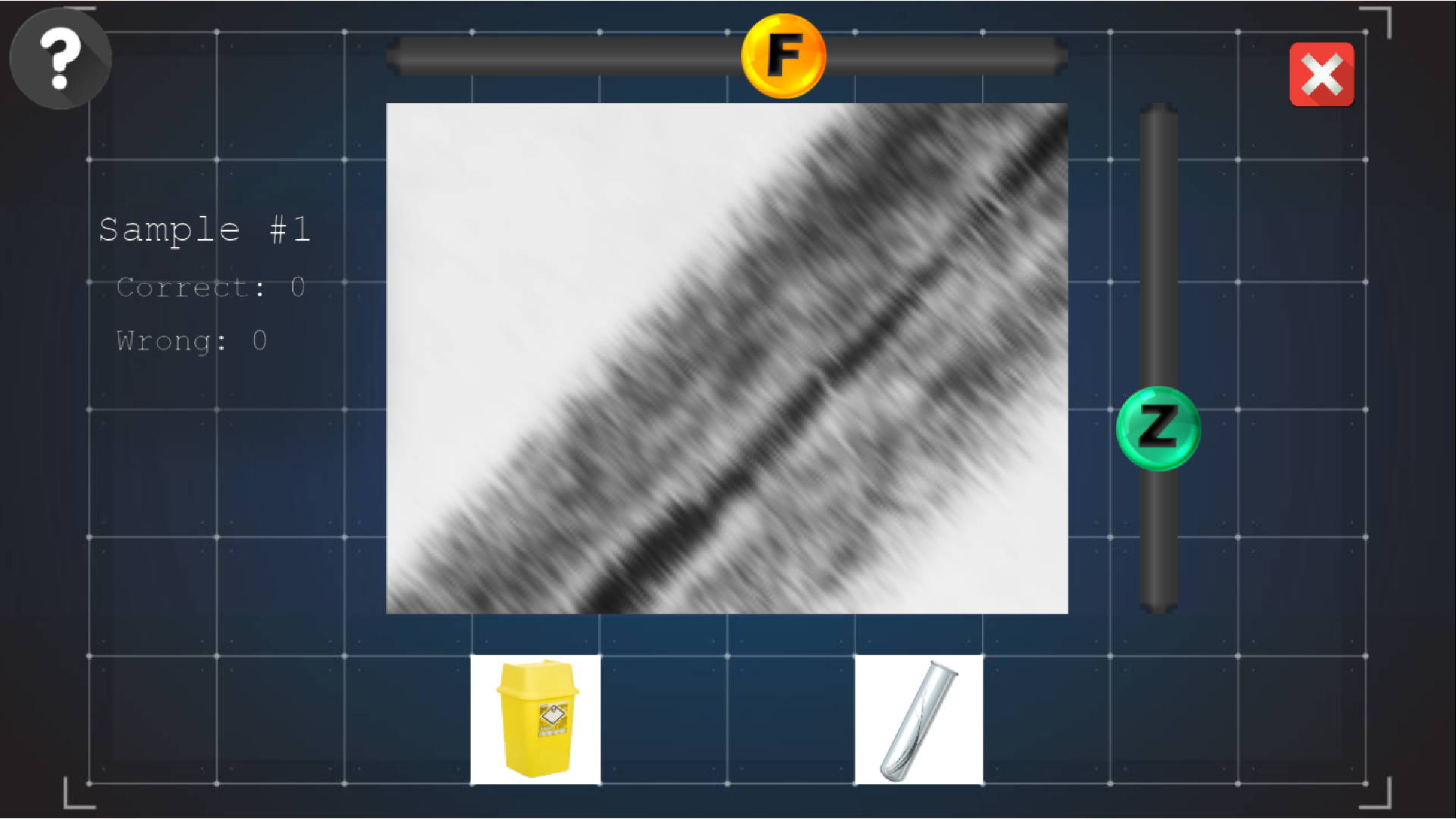

Microscope

The microscope allows players to examine a number of hair samples in order to figure out which are human and would belong to Cynthia. This is for both drug-testing and for DNA analysis. Turns out not all hair strands are suitable - you’ll have to play the game to learn which :)

The microscope has zoom and focus controls. This allows players to get a good look at the hair before deciding whether to keep it for analysis or throw away.

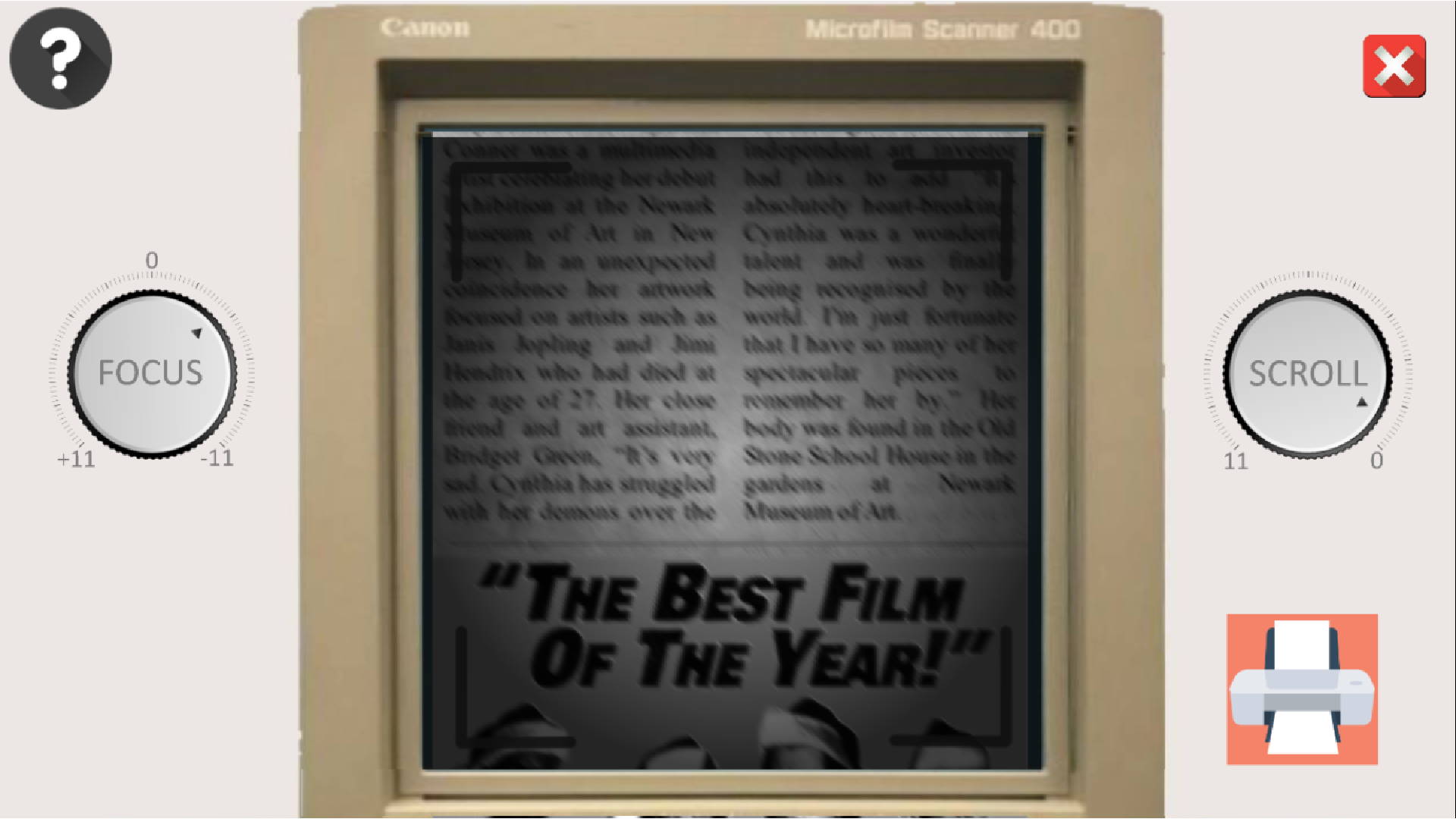

Microfilm

The Microfilm reader has some similarities. In that, players can scroll a long piece of Microfilm in order to view news stories from the date of Cynthia’s death. I reused the focus idea from the Microscope and made the Microfilm slightly faulty - in that sliding the film through causes it to lose focus so the players need to refocus before they can read (or print) it.

Originally, it required players to figure out what was relevant evidence to the story. I give them a bit of a helping hand by telling them whether they need to scroll up or down to find the important information.

Mystery Development

One of the biggest challenges is that this is firstly a murder-mystery. So, creating characters, motives, timelines, story and a script that works is the first problem. Then figuring out how we are going to reveal this information to the players - some is suggestion, some is fact. And then how do the puzzles and objects feed into this. Also, a big chunk of the information is coming from the suspects themselves – the players get to experience it through the lens of the suspects. These characters are able to twist the facts to suit themselves. How is the player able to know who to trust and what parts are facts?

The WHY question?

Plot-holes in mysteries are a personal bug-bear of mine. Even in traditional narrative forms - making a story unfold in a satisfactory way for the audience is very difficult and it often results in characters doing things that don’t really make sense. Asking ‘Why’ a character is doing something at any point really helps with this. What is their motivation for this? And does it break how they have performed in the past? They should have consistent behaviour (unless something has happened to the character to change that).

This means that I usually start with a short story version. What is the definitive description of events that happened (i.e. on the evening of the death)? Who did what at what time and why were they doing that?

The next question is deciding how to reveal these details to the audience / players. The revealing might be done through evidence that we find or it might come through other characters. Which character is doing the revealing affects what lense are we seeing this information through. If it’s a murderer who is revealing information to us then clearly they will want us to see a certain series of events.

Typically, in any mystery you can be sure that every character has something to hide. This explains their reluctance to help the investigator. Usually, in mysteries it’s a case of figuring out what each character’s individual secret that they are hiding.

Technical Challenges

I don’t normally cover the technical details of my projects as it’s not usually that applicable to my audience. So this is a bit of an experiment - but I’ve tried to keep this lite on technical detail still .

Choosing the game engine?

I had hoped to reuse (or at least use as a starting point) some technology that I’d recently built for another game: Lost and Found. This is based on separating the game into chapters (or locations) and then an SMS messaging system that moves the game forward - managing communication between the player and their main assistant. Evidence comes through the assistant collecting items and then the player tries to interpret it. It supports multiple branching stories. And it was fairly well tested as it was about to launch another project.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t as well received as I’d hoped - so definitely a back to the drawing board moment which meant me exploring alternative web technologies that we could build a game in quickly.

Side Note: Something that I keep failing to do is reuse the technology from another project. I spend so long getting everything together for a project deadline and always being right up against it. It would be nice to not start from ground zero each time and therefore have longer to expand and refine things.

It’s always difficult to find the right engine when making HTML5 games. Usually, it depends on the type of game that you’re making as to what is the best fit.

- GameMaker Studio 2

- Unity

- TyranoBuilder

- Construct 3

- Godot

- Phaser

We had used Tyrano Builder Visual Novel Creator for a previous online Escape Game - and while it worked well when the game was simple - it was more time consuming to use this for something more complicated.

Ultimately, I chose GameMaker. It’s an engine that I used 15+ years ago to teach children to make games quickly and one that I also used in First Year Undergraduate teaching. It’s come on a great deal in this time. I liked the HTML5 export (although this is an add-on purchase).

Zoom - videos

We’re using zoom screen sharing extensively throughout. It works wonderfully well. But it requires our players to complete a few steps themselves. Start the game in a web-browser, screen share the correct window (with audio) and then go to full-screen. As with any set of simple instructions some players will absolutely fall at this hurdle.

In addition, we’d want them to be running a newish version of zoom and kill other programs and tabs.

The player performing the ’navigator’ role needs both a reasonable spec computer and internet connection. We’re not talking top of the range here - I’ve got a bunch of mid-spec laptops that are almost a decade old that it runs fine on. But many people have laptops with slow-cpus, low amounts of memory or have just installed far too much on. If the game experience is poor on these then it is still our problem.

I had visions of streaming HD video of our suspects to all the players in the breakout room. It quickly became apparent that this would be too much for many people’s machines.

You need to remember that any time the navigator machine is:

- downloading videos of the suspects

- playing these locally

- recapturing the screen

- broadcasting this capture to other players

- capturing their camera/audio and sending it

- showing video / audio of other players

There’s some small things we can do to reduce the load - such as getting our navigator to switch off the camera. It’s also possible to play with Zoom settings (such as optimise for video) - although this is another headache for our players to deal with. The ‘optimise for video’ setting is an interesting one as it ensures a better frame-rate but at lower quality. The issue being that once it’s decided to reduce the quality it doesn’t restore it - so other players are left with a pixelly display.

So the two big issues are to reduce the size of video downloads and reduce the capture for upload. It’s frankly amazing how good video compression is and just how small you can make video files that are still very usable - sometimes this is at the expense of CPU decoding time. Figuring out the best combination of video and audio codec for the web takes some playing with. Secondly, the more screen space they videos are displayed at - the more work it is in terms of capturing and sending the results.

Originally, I thought that having quality options that the players could change themselves but it was just another layer of complication that the majority of players didn’t want to deal with. Instead I settled on a single setup that worked for the vast majority of users. Lowest common denominator.

Videos

Game Maker doesn’t support videos playing in HTML5. So, that’s a bunch of javascript code which overlays videos in the right location on top of the rest of the game.

User Interfaces

User Interfaces are boring to create and time-consuming. GameMaker doesn’t have great support for them. I did find a fantastic add-on that helped with this: Shampoo by Zack Banack.

While Shampoo is absolutely excellent and the project would have hugely suffered without it. Unfortunately, it couldn’t do everything I needed so then there’s work to get that working with my own User Interfaces.

Advanced Mini-games

I loved both the microscope and microfiche puzzles. There was a huge amount of work to make this work seamlessly - behind the scenes they use shaders to handle the zooming and the focus.

And then there’s some complicated tasks which no one even knows were solved. e.g. scrolling through a long newspaper (on microfilm) created a texture too large for GameMaker. So, splitting this up into multiple textures and seamlessly rejoining them together is a fiddly problem that no one knows exists.

Screen resolution

I’m not the biggest fan of making games for variable size screens. It’s already a pain on mobile but web is even more awkward. Do things scale, stretch or have borders around. Are pieces of the User Interface locked to particular areas on the screen?

Optimisation

The early builds of the game were very large. This meant that when players started the game there was a long delay while it loaded. Optimising content to ensure fast loading is often challenging. One big win was that GameMaker can organise your art assets onto texture pages (aka texture atlases) - but it does so as png files. While png are essential for User Interface components and those with alpha - jpegs are generally much smaller. I was able to organise all the images suitable as jpegs together and then convert them to lower quality jpegs. Although, they still needed to have the .png file extension :D I

Design Challenges

Artwork Challenges

Art is definitely not my strong point - but I can do just enough to be dangerous. With more time - having someone dedicated to this would have been a massive benefit. It’s hard when puzzles, story, script and code are all moving at the same time. Sometimes it’s much quicker to do it yourself. This has worked well for me in the past and then to have someone else come in and spruce it all up once we’ve got a working prototype.

Locations

Even the locations required my ‘photoshop skills’ to remove existing exhibitions in the galleries and other spaces. Some of the museum objects and paintings did not have permission to be shown online. It was cheaper to have me edit them out - than to have the galleries emptied and then re-photographed. Look closely and you can probably spot this - my photoshop skills aren’t that strong!

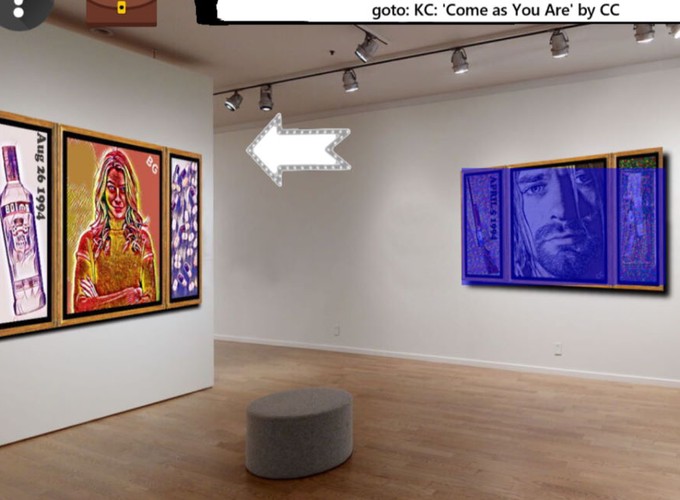

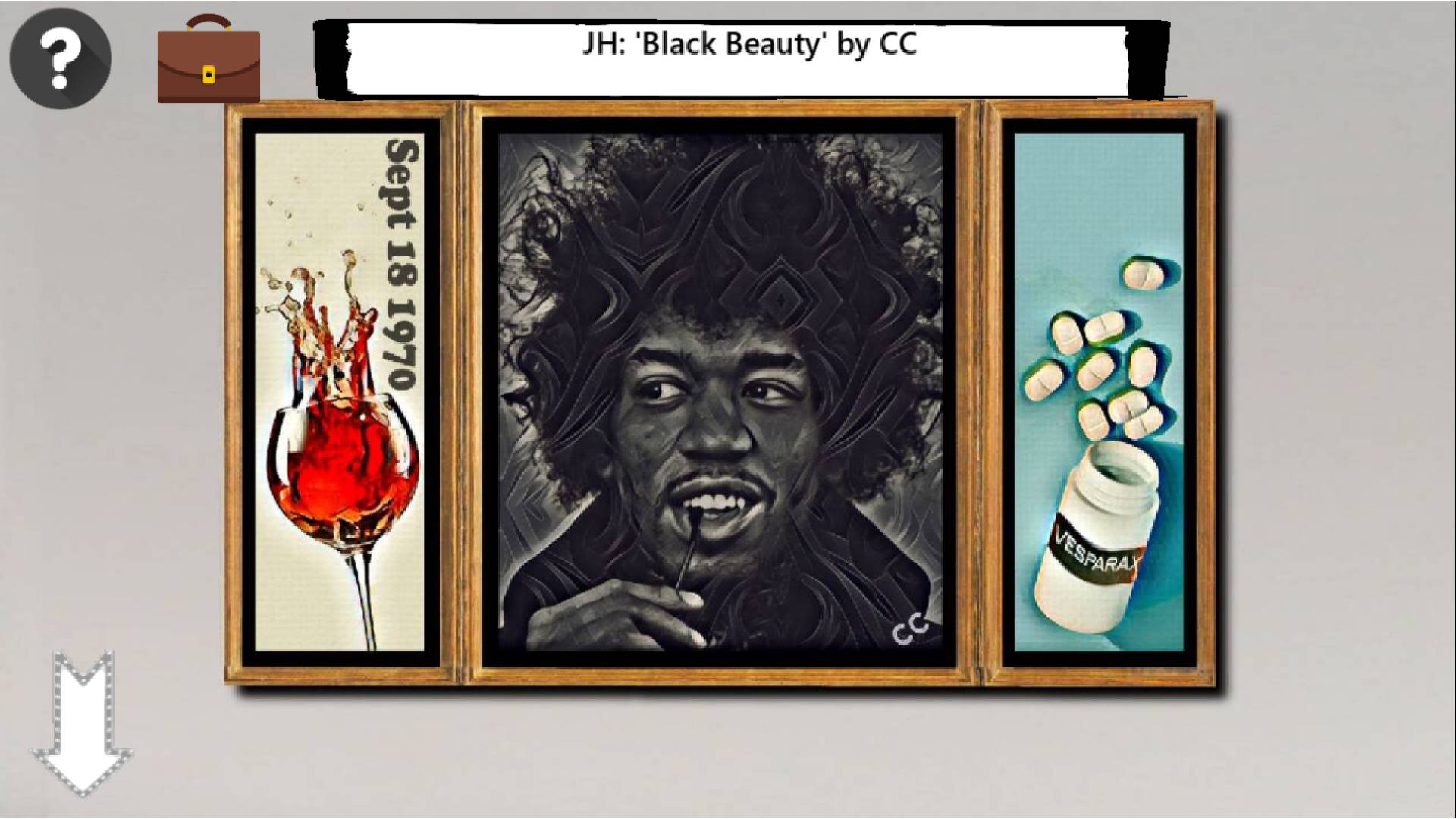

Cynthia’s Art Exhibition

I had to create all the pieces that are on display painted by the characters: Cynthia and Bridget. I think this will be the closest I will get to my own artist exhibition! It turns out researching your characters and trying out different styles takes a long time. I eventually decided on a Triptych style with the focus in the central frame and then items linked to their death in the smaller frames. I used AI style-transfer in order to create the different painting styles. I generate a collection of different ones before deciding which I felt looked best together. Simple - not forgetting that each painting has some meaning in the game and potential use in the puzzles.

This is the closest that I will come to being an artist and having my own Art Exhibition - even if it is only virtually. Fortunately, even those of us with close to zero artistic talents can create engaging virtual exhibitions. Many players will spend time simply enjoying the artworks in their own rights.

Puzzle challenges

I always maintain that making puzzles is easy. Anything can be turned into a puzzle without too much work - the real challenge is making puzzles that make some kind of sense in the real world. We don’t really come up with many puzzles in our day-to-day life - so we are always bending reality in that sense. But, the puzzles should at least be able to answer our WHY? question from above.

Player Collaboration: Navigator vs Observer

Originally, I envisaged that player collaboration would happen naturally. There is a lot to keep your eyes on in terms of what the characters say. I think this works well if all the players know each other up front - it’s natural to speak-up and tell your friends / family what you want them to do. When you are playing in a team with people you don’t know - it’s much easier to take a back seat. This was even the case with American players - who I usually find are more amenable to playing with strangers. In early play-tests - players made comments that they didn’t feel engaged enough with the team. I had hoped that the phases in the game where you debate what has happened would help this.

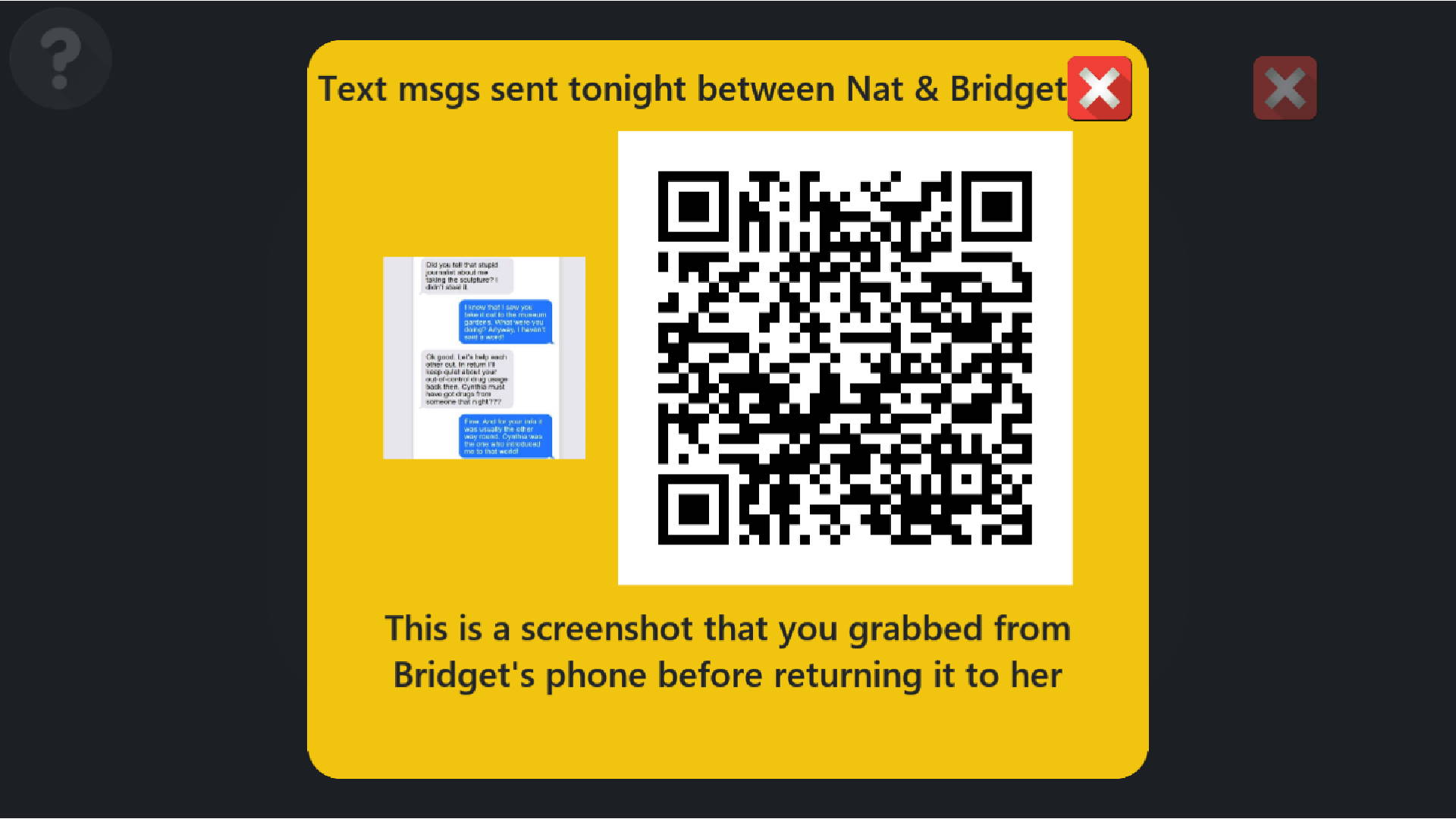

If you’ve read other blog-posts on here you’ll have heard me talk about multiple points-of-interaction. Basically, allowing multiple players to interact with the game simultaneously. These don’t need to be equal in standing but they do need to provide agency. So, Plan B was always to incorporate the QR code-system that we used in Ballantine House. This enables the non-navigator players to be more involved. They can investigate evidence in closer detail - something that isn’t in the web-based component of the game. It requires those players to examine evidence and discuss it with their team and therefore forces their involvement in the game.

Challenges of the brief

Originally, it was designed to replace a real-life murder mystery that takes place in the Ballantine House (a stately home). The kind where the staff are dressed up as characters and have a script to work off. So, taking this from an real-world experience to an online Zoom-based one but still with an army of live actors. The idea was to end up with a Cluedo meets Zoom experience (Fun Fact: Cluedo was developed in Birmingham by Anthony Pratt). Since the addition of breakout rooms to Zoom, the transition could be reasonably straight-forward. Museum staff can be placed into different rooms within Zoom and the players can move between rooms (either managed by the host or self-managed by players). Players can speak directly to the characters or listen in the background.

I had some ideas to make this feel less like a Zoom call.

- Having a web-front end that presents players with a map of the house. Clicking on rooms allows players to navigate to different spaces.

- Some rooms contain characters and others contain puzzles

- As players progress, they are able to ‘unlock’ other areas of the House and get a sense of progression

A new constraint was added that it could only be run with 1 or 2 hosts. This meant a change from live interactions to video recordings.

There were also concerns raised about both it’s staff and venue being associated with a murder - even a fictitious one. This meant we had additional constraints to address:

- Couldn’t be a present day murder

- Couldn’t involve museum staff

- Murder not in the main building

Honestly, I was concerned about the change in the project direction from my earlier understanding of it. Fortunately, the small team from the museum that were working with me were very positive and full of ideas. So, we pushed forward! Together we managed to address the concerns of a murder taking place at the museum. The eventual compromise we reached was:

- setting the actual murder almost 3 decades years ago

- having it be more of an outside hire event rather than closely associated with the museum

- having the murder take place in an outbuilding

- the target and suspects weren’t museum staff

While, I really liked the scenario that we’d come up with to address these constraints - it’s certainly more difficult to bring players up to speed with the story quickly. It’s much easier to say - a murder has happened this evening and the suspects and clues are still here. Rather than a murder happened 27 years ago and we’ve managed to get everyone back together. It also creates a real grey-area around clues. There’s a lot of story-world to front load to get players up to speed with things. Some experienced players love this additional challenge but this was a lot for our audience to take on.

The early conversations were around a target audience of the 18-40 age range. This was extended to a suitable for all - and certainly within the museum supporters there are a lot in the older range. Ultimately, this meant removing some complexity and player freedom to simplify the game to make it easier for all. What was pleasing was the feedback from these players was very positive.

And finally, there was an additional requirement that the game had to deliver on the science content front. This was an area that I kept getting wrong. It sounded like this was a very important goal but I struggled to get clarity on exactly what this meant - only that it needed to be more educational than our previous game ‘Escape from Ballantine House’.

Game Production is Hard!

Games are some of the hardest things to make. Mainly because the budget is usually fixed but the success criteria is so woolly. You can build all the component parts and it can function fully as a game but the client can still be very disappointed in the outcome.

This doesn’t even include the additional challenges of play-testing and bug-fixing. Because there are so many ways that a game can be played there are so many ways that things can go wrong.

I worked 100-hour weeks at Codemasters almost 20 years ago and this was the first time I had to go back to this. I think if you looked at the finished game - you might wonder why it took so long. I look at it and wonder where all the time went. Fortunately, I log everything so I have a pretty good idea. But you’re not just making this one finished game. We made probably 8 different versions that were shown to players - and each time this means that code, art and audio changes. Lots of this doesn’t even make it into the finished game. Puzzles and locations that we liked and invested time into have been thrown away.

The script was re-written on 5 occasions, re-filmed by volunteers where needed. Then these video assets need to be re-processed and added into the game - along with the data to tie them up.

I always struggle with communicating just how much work is involved in making a game. One issue is that there is just too much to do (common on non-game projects too). A second issue is that even once you’ve got a working version you’re still a long way from ‘release’ – as I mentioned before you can only gather feedback once you have something to show. Thirdly, it’s usual to put off all the minor issues to the end of the project. Often you have a long list of small problems – many which are very time consuming to solve. And finally we need to test it on different hardware to what the game was built on – and this will throw up a bunch of new problems on different machines, browsers and screen sizes.

This was a genuinely 16 hour days, 7 days a week project. It has:

- 50 rooms

- 8 mini-games

- 8 web games

- 100+ Character Scripts (over 5000 words + re-edited and re-recorded)

- 74 videos (cut down from over 120)

- 5 pieces of art (triptych)

- I wrote 5000 lines of code (not a very useful metric I know)

- 80 UI panels

- some music, speech & sound effects

- and a partridge in a pear tree!

Here’s a rolling slideshow of most of the graphics used in the main game:

Simplify!

The concerns from the early play-testing were that the game was both too long and too difficult for their intended audience. It was originally pitched at an 18-40 audience who are both computer savvy and have some knowledge of Escape Games or online games.

It’s hard to make something that is both complex and rewarding with a short play-time. It takes time for players to ‘get into’ an experience, to learn the rules of the world and get immersed. At the same time players can hit game fatigue if the experience is too long. Typically, 45-90 minutes is usually the right ballpark for most teams. Less than 45 minutes and players see the experience as shallow and question its value. Above 90 minutes players are getting tired and will want a break. Aiming for around an hour is about right - although this is complicated by teams of varying abilities.

The biggest fix was removing some of the player freedom. Originally, players could wander freely around the space which got larger as new areas opened up. By restricting movement to exactly where they needed to focus, this sped things up a great deal. So, just as areas would open up - we’d also close off other sections.

In addition I added a big pink hint marker. If you see a Pink Magnifying Glass on something that means there’s a puzzle there waiting for you to solve. It’s a bit like shining a big spotlight on it :)

Some chunks of the game got cut - which is not as simple a process as it sounds. Unfortunately, you can’t just highlight a block of the game and press the delete key. Everything interacts with everything else. This means that there’s still a bit in Act 3 that I’m not quite happy with.

Ultimately, these changes remove some ‘player freedom’ – stronger players will be disappointed at this but it means that weaker players are more guided to the right answer.

- Characters are a bit more obvious and have less subtlety to their performances

- Players cannot really interrogate characters (originally - there was a multiple-choice to the questioning)

- Mini-games have been made easier. Originally, it was possible to fail and repeat them

- The environment has been reduced in size. A few rooms that players moved through and the museum archives were cut

- Rooms close off once you don’t use them anymore. This required a re-jigging of the environment layout - but once an area is completed you can no longer return to and be distracted by it.

- More hints. Items of importance are more obvious.

Murder Mystery –> Escape Game

The brief started out as a Murder Mystery experience. However, it became clear that this was too subtle an experience for their intended audience. It became very apparent that it needed to be much more interactive and with fewer observation puzzles. This meant a switch from interrogating the suspects to more evidence gathering mini-games.

It constantly felt like we were walking this tight-rope between Murder Mystery and Escape Game. Escape Games are essentially very puzzle heavy and players become very focused on seeing and solving puzzles to the extent that they switch off and miss anything that isn’t directly puzzle related. This means that players often miss aspects of the story – which in the case of a murder-mystery is very important. I was reasonably pleased with the outcome but it’s certainly something that I’d like another go at.

What Next?

Now I’ve had a bit of a break from the development - the Murder-Mystery / Escape Game is certainly an idea that I’d like to revisit. I’m a big believer in constraint-based-design and it helps you get to something unique as you need to innovate against these boundaries. I’d like to soften some of these (e.g. not a retrospective murder) and choose a more targeted audience.

The Zoom platform is constantly evolving - and tools such as screen-sharing directly into break-out rooms would have been a nice addition if they were available at the time.

Additional monitoring tools to see what the players are up to would be a big improvement. Currently, game hosts pop into Zoom rooms to check on the players - which works well but doesn’t scale to larger groups. It’s something that I usually devote time to - but we were already a long way over schedule.

There’s certainly a whole bunch of areas that could use another round of polishing. Usually, this means ‘juicing up’ the graphics, UI, feedback, better audio etc. For example, the UI and shadow characters were placeholders that never got replaced :)

I also think I would like to explore a shared ending. The players start as an entire group and I think it’s nice for them to finish as an entire group.

More easter eggs / clues. I usually like to reward players who have explored that bit more and observed that bit better - but there’s not quite so much in WKCC.

A Monumental Team Effort

Obviously, a game like this doesn’t happen in a vacuum - it was absolutely a team effort. Massive thanks once again to the team at Newark Museum of Art for having the vision to commission and collaborate on something which is certainly radical within the museum world. From ideas for theme, science, story, character, puzzles, general feedback and even staring in the game - it was the same team as worked on Ballantine House: Silvia, Maegan, Shirley, Tim, Kirsten and Rey. Silvia gets a special mention for being the Script Doctor and Maegan for overall production and overseeing the casting for the actors. Huge thanks to our very talented actors who really brought the characters to life!